1700s - research & making - Queen Anne Silver - eye sight loss and ironwork

- Stephanie Smart

- Nov 1, 2025

- 19 min read

Updated: Dec 1, 2025

Silk history

"The Political Register reported that, during the Calico Crisis three thousand weavers and their families “Crowded the passages to the House of Lords of whom they demanded Justice as they pass’d by." Silk should be favoured over calicos, it was argued, because printing on cotton employed fewer people than the various stages of throwing, dyeing and weaving silk. Calico printing employed only 800 people, compared to the 16,000 weaving looms estimated in London and the 3212 apprentices bound in the city during the 1710s."

Royalty

Queen Anne - was the last Stuart Queen. She was Queen Mary II's younger sister and had not been expected to succeed her. She ruled after the death of Mary and her husband, William III, from 1702-1714. Like Mary, she left no living heirs, despite 18 pregnancies.

Queen Anne Silver Research

Silk and money, or more accurately textiles and money, have always gone hand in hand. Fortunes were made in Britain off the wool trade but silk seems to speak of money more directly than any other fabric. I am looking to reflect this in the design and making of Weaving Silk Stories, my collection inspired by the history of silk (the design, manufacture and trade there of). Making the collection in association with Historic Royal Palaces is arguably, historically, an entirely authentic undertaking as the Royal Court kept British silk weavers in business for centuries. It was in Britain's royal palaces and grand stately homes where silk would most assuredly have been worn (and hung and draped across the interiors) during the16th and 17th centuries. Silk is however interlinked with Royalty and the upper classes not only through their direct wearing of this very costly fabric but also through the ways in which the story of the building of the whole British banking system is interwoven with the trading of textiles. To hear this story I would recommend listening to the podcast by Haptic & Hue titled: A Feeling of Wealth This history is visually born out in the layout of the City of London where the Bank of England is located just a few streets from the the halls of the Worshipful Livery Companies including the Mercers, the Clothworkers and the Weavers all of whom were implicate in the making and trading of textiles. This area in turn is just a stones throw from Spitalfields, the silk weaving centre of Britain in the 1700s. Certain garments that were made from silk (such as the very wide dress known as a mantua) were designed quite simply to show off wealth. They were designed to the ends of displaying as much uncut silk fabric as possible. You might as well have had your husband's bank balance written across your skirt for all to see when you went out in public wearing one. But likewise poverty, a distinct lack of money, is part of the story of the history of silk, not least in terms of the wages of the weavers involved at various stages in this history. I will touch on that more in other posts.

Therefore I decided early on to reflect money as directly as possible in the appearance of certain pieces. Hence the dress in this collection titled Cloth of Gold alongside this one Queen Anne's Silver.

In the decoration of the Painted Chapel in Greenwich (shown below) Anne can be seen portrayed with her husband, Prince George of Denmark who was Lord High Admiral of the Seas (around them are figures representing: Asia, Africa, America and Europe). The painter Thornhill also surrounded the royal couple with deities such as Neptune. This emphasised the importance of Britain as a naval power, by which an empire would be built. The trade of textiles and other precious items were part of this but likewise the, less commonly appreciated, strength of Queen Anne's reign (and marriage). Historians have sometimes been unkind to Anne (focusing on her weight and her obsession with the Duchess of Marlborough) but Anne was seen as an effective ruler able to balance the needs of the many different factions around her.

Here she is portrayed alone:

You can listen to a wonderful podcast about Queen Anne made by Historic Royal Palaces here

Anne's primary legacy is undoubtedly the union of England and Scotland in 1707.

"While Ireland was subordinate to the English Crown and Wales formed part of the kingdom of England, Scotland remained an independent sovereign state with its own parliament and laws...[until]...England and Scotland were united into a single kingdom called Great Britain, with one parliament, on 1 May 1707" https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anne,_Queen_of_Great_Britain

Portrait from the school of John Closterman, circa 1702

"Deeper political integration had been a key policy of Queen Anne ever since she had acceded to the thrones of the three kingdoms in 1702. Under the aegis of the Queen and her ministers in both kingdoms, in 1705 the parliaments of England and Scotland agreed to participate in fresh negotiations for a treaty of union...The Kingdom of Great Britain was born on May 1, 1707, shortly after the parliaments of Scotland and England had ratified the Treaty of Union by each approving Acts of Union combining the two parliaments and the powers of the two crowns. Scotland’s crown, sceptre, and sword of state remained at Edinburgh Castle. Queen Anne (already Queen of both England and Scotland) formally became the first occupant of the unified throne of Great Britain, with Scotland sending forty-five Members to the new House of Commons of Great Britain, as well as representative peers to the House of Lords".

At Hampton Court Palace this Union is memorialised in ironwork designed by Jean Tijou:

The Hampton Court screens From Jean Tijou's book of 1693

I am including mention of Tijou's work here because there is in fact a strong thread of connection between the mastery of metalworker and the history of silk in the UK. Jean Tijou's skill is an example of one of the many other skill sets that Huguenot refugees bought to Britain. You can read of the Huguenot's undoubted expertise in silk weaving and the importance therefore of their input to the UK's silk industry here

"Jean Tijou (fl. 1689–1712) was a French Huguenot ironworker. He is known solely through his work in England, where he worked on several of the key English Baroque buildings. Very little is known of his biography. He arrived in England in c. 1689 and enjoyed the patronage of William III and Mary II...he was titled as England's Best Wrought-iron Designer. He was employed at St Paul's for twenty years...He left England for the continent c. 1712." " https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean_Tijou

Anne and the French:

Despite his Huguenot heritage there may still seem a great divide between metal work and silk weaving. But this is bought into question by Elfrida Sellick in her article about William Folliott, artist, designer and Master Weaver (1835 - 1925). William was also a Huguenot and Elfrida considers, first of all, the weaving done by his father (likewise named William Folliott) who was also apprenticed as a metalworker. She tells us that:

"William Folliott...who in turn was the son of William Folliott the Shoemaker...was indentured on the 9th October 1821 to one John Louvel to serve as an apprentice weaver for a period of seven years. It is interesting to note that William the Shoemaker also indentured him to the same John Louvel as an apprentice blacksmith on the 1st November 1821. It would therefore appear that there was some doubt in William the Shoemaker's mind as to where his son's talents really lay, particularly as he was at that time only sixteen years of age, having been born in 1805, the year of the Battle of Trafalgar. Fortunately for the Folliott family, William the Younger chose to become a weaver, no doubt influenced by the evidence of the weaver's art all around him in Spitalfields...Although at first sight the crafts of blacksmith and weaver are poles apart, in practise this was not so. The blacksmith was in great demand in Spitalfields to produce castings for and repairs to the looms of the weaving community. In some cases a man would augment his income by combining the two crafts."

Many of the posts I am writing detailing my research for the various pieces that make up the Weaving Silk Stories collection cross reference. You can read more information about the youngest of the three William Folliott's mentioned in Sellick's article in my post for Cloth of Gold because he would become a Master Weaver and the chief designer at the silk manufacturers Messrs. Warner and Sons. And in this role he would be responsible for the weaving of garments of state including some for Royal coronations. He may also have been responsible for this thistle and rose design (later made in wool and cotton) held at the V&A: https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O258203/rose-and-thistle-furnishing-fabric-warner-and-sons/

Which all ties in nicely with Jean Tijous use of these same symbols of the Union in his ironwork.

There are many examples of designs for royal silk garments with decoration that has these symbols integrated into it as surely as did the metalwork:

please click on each image to be taken to source

I knew I wanted to therefore integrate the thistle into the design of the dress this post is concerned with. The dress that would be titled Queen Anne's silver . The symbol of the English rose features in the design of the dress Support thoughts of roses. But I also planned to incorporate the design of the chain around Annes' neck in the Closterman portrait of her (above) and it likewise incorporates the shape of the English rose. Somewhere I was aiming to include the harp of Ireland as features also in Tijou ironwork, would that be here or elsewhere, I wasn't yet sure.

I found thistles in illustrations from the period such as this beautiful drawing by Maria Sibylla Merian whom I talk about in depth in my post Mulberries in Fournier Street

You can see one in the Royal Collection here https://www.rct.uk/collection/exhibitions/maria-merians-butterflies/the-queens-gallery-buckingham-palace/milk-thistle

And there is this full flowered one:

In the end, however it was this image, an illustration dated to earlier in Queen Anne's life, that won out, for use as my inspiration.

Vol. IV, F.157 Carlina acaulis L.

Stemless Carline Thistle Paris c.1670

"No other botanical manuscript in the Austrian National Library is as luxuriously presented as the ten-volume Codex Miniatus 53, here referred to as the Florilegium of Prince Eugen of Savoy..."

- possibly by Nicolas Robert 1614-1685 - A Garden Eden H.Walter Lack pub. Taschen

I chose it in part because it was created in the early 1700s but in part because of pure aesthetics. It shows a wonderfully unique angle on this plant.

Silver silk dresses

There were three reasons why I would choose silver for the colour of my Queen Anne era dress and the first may (at first sight) appear strangely unrelated.

1) Eye sight loss:

In my post Blindness, deafness, knock knees and hump backs I write more about the research I have done with the RNIB and The East Cheshire eye society because of the eye sight loss suffered by many silk weaving workers. During that research I found out that some people suffering with visual impairment find it easier to see items (and text) that are coloured with contrastingly bold colour combinations, eg black and white. I explore this colour combination in relation to male fashion in my posts Decorated Men and Mulberries in Fournier Street. Instead of settling therefore on that exact mix (as it was in fact applied to the costumes in the feature film about Queen Anne The Beloved) I decided I would use silver with either black or royal/navy blue for this piece. The reason that eye sight loss is particularly relevant to mention as part of my research for this piece is because it turns out that, whilst significant achievements can be attributed to her reign, Anne:

"...was also a sickly child, [who] may have suffered from the blood disease porphyria, as well as having poor vision and a serious case of smallpox at the age of twelve. Poor health would plague Anne her entire life, probably contributing to her many miscarriages."

Culturally the period of Anne's reign is not accredited with much import but it is possible that she was incapable of leading decision making regarding the aesthetics of the time because she was struggling to see. She has been criticised for being a prudish, plain and pious queen. It is considered possible that when she was a younger woman she was a little more glamorous (though always the plainer of the two sisters) but I only feel more sympathy toward her for all that. Because any truth in the matter was likely impacted by her poor vision and was also no doubt driven, at least in part, by by the fact that she suffered through at least 17 pregnancies. Only one of Anne’s children survived beyond infancy. William, Duke of Gloucester died of

smallpox at Hampton Court Palace at 11 years old. By the time she became queen Anne was likely in constant pain with gout, obesity, a notably reddened complexion possibly caused by lupus and the inability to walk far. Also, not only was her eye sight poor as an adult, but in fact...

"...As a child, Anne had an eye condition, which manifested as excessive watering known as "defluxion"..." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anne,_Queen_of_Great_Britain

...which continued throughout her life. To hear more about Anne's appearance please click here to listen to a podcast by Historic Royal Palaces. Those are quite some odds to have stacked against your ability to drive a country forward and yet she did so.

I find the facts about Anne's life and health so interesting because of the way they link a member of the Royal family (who would have dressed in silk) directly with the commonly experienced ill effects of being one of the workers who made silk for the wealthy at this time and in later generations.

Unlike Elizabeth I Anne is not noted as a great Queen. Nevertheless it was during her reign that Britain started to become a great power and this should be recognised. I photographed this sweet portrait of Queen Anne as a child with silver trim on her dress on my second research visit to Hampton Court Palace.

Image: Queen Anne (1665-1714) when a princess c1668-70,

Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

You can read more about Anne's life here: https://www.hrp.org.uk/kensington-palace/history-and-stories/queen-anne/

Note: I found it interesting to come across this document signed by Anne,

thereby to see her hand-writing (I like putting text directly on the surfaces of the

garments I make from paper:

Despite the generally despondent attitude adopted regarding Queen Anne's cultural impact in 1710 she commissioned architect Sir Christopher Wren to remodel the Chapel Royal at Hampton Court Palace. He placed a grand timber reredos (altar screen) over the brickwork that had covered space left by a destroyed stained glass window that once filled he east end of the chapel, depicting Henry VIII, Katherine of Aragon and Cardinal Wolsey. It was destroyed in the Commonwealth. It was the shapes in the ceiling design of the chapel that most intrigued me and I believed I would go on to integrate them into the design of the dress as a texture to be appreciated by people with sight loss and to link with Tijou ironwork in the design shown below.

© Historic Royal Palaces

To read more about Hampton Court Palace please click here

In fact in the end it would be the shapes in the Queen Anne era chandelier at Hampton Court Palace that I would decide upon for the raised texture I planned. Light after all has always been key for anyone looking to preserve their sight whilst designing, making or crafting work that is detailed and precious. Hence why the windows in the attic rooms of the Spitalfields silk weavers needed to be so large as you can see here

The chandelier is glorious, with its thick silk rope (another example of the skill of those working in the arena of passementerie for interiors and fashion, a heritage skill set I would be looking at in detail)

2) Queen Anne Silver

I do have to admit that it was only once the decision to use silver as the colour of the dress had become fixed in my mind that I discovered there is a range of silverware called Queen Anne silverware. But it is a nice serendipitous link. For examples please see https://www.acsilver.co.uk/shop/pc/History-of-Queen-Anne-Style-d316.htm

"Queen Anne silver is also known for being of an exceptionally high quality. This is accredited both to the emphasis that was placed on construction, and the influx of skilled Huguenot smiths during this period. Huguenots were refugees that fled France in search of safety when the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes occurred on October 22, 1685. They emigrated to various lands, bringing with them their expertise in a vast number of trades, including silver. Among the estimated 200,000 to 1,000,000 Huguenot refugees that settled outside of France was David Willaume, one of the most successful and prolific smiths of this time. The remarkable skills of the Huguenots proved to be incredibly influential, and this is reflected in the European inspired nature and extraordinary quality of Queen Anne style silver."

You can read more about Huguenot Silversmiths in London, 1685-1715 here: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5302&context=etd

3) other silver dresses:

In fact from early on in my research for this project I noticed a seam of silver running through my visits to see historic silk garments from the periods of history I was considering.

Here are some of the silver dresses I saw in paintings as I looked across the late 17th to early 18th centuries and on beyond Anne to the next dynasty that would follow hers (The Stuarts), ie. The Hanovarian legacy of George's II, II, III and IV:

There is this one from the Tate collection:1650-5 Joan Carlile Portrait of an Unknown Lady https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/carlile-portrait-of-an-unknown-lady-t14495

ca. 1659-99 - Jacques Laumosnier (French, c. 1669-1744). The interview of Louis XIV and Felipe IV in the island of the Pheasants, . Oil on canvas; 89.1 x 130 cm (35 x 51.1 in). Le Mans: Musee de Tesse, LM 10.101. Source: Wikipedia

1659 - Sir Thomas Fanshawe of Jenkins (1628–1705), and His Wife, Margaret (1635–1674)

LDVAL10 gift from Aubrey Fanshawe 1963

Photo credit: Valence House Museum

And one of the most stunning Royal silver dresses is the Rockingham mantua which you can learn about in much more detail here

1760 - Worn by Lady Mary Rockingham probably to the investiture to the Order of the Garter by her husband Charles Watson-Wentworth, 2nd Marquess of Rockingham. He opposed John Stuart 3rd Earl of Bute who was minister during the early years of the reign of George III and referred to his wife as 'my Minerva at my elbow.' Shown at Kensington Palace as part of Court to Couture exhibition Summer 2023 © Royal Ceremonial Dress collection

You can read more about its history here

You can see a video of a research trip made to the Royal Ceremonial dress collection to see the Rockingham mantua here https://www.hrp.org.uk/schools/learning-resources/georgian-court-coat-in-depth-video/

Then I saw this image being sold by a company called Diktats and I was highly intrigued:

"Engraving by Nicolas de Larmessin I representing a jeweller. This engraving belongs to the famous series of Grotesque costumes and trades. This proof published by Larmessin belongs to the first edition of the suite published in 1695. The different objects sold by the jeweller are listed in the images: chandeliers, gold and silver snuff boxes, from Venice, from Dieppe, from tortoishell, from ivory, miniature fans, canes garnished with gold and silver "pagotte" from China and other monsters of gold and silver and several fashionable jewels"

It was in this way that I discovered the work of Nicolás de Larmessin I. To see more of his amazing costumes designed to represent and reflect many different trades please see https://www.mutualart.com/Artist/Nicolas-de-Larmessin-II/B7497A4EDC238C9E/Artworks

The Welcome Collection holds the image of Medicine, Pharmacy and Surgery:

and at Christies there is: https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5963193

This mantua from 1700 is similar in style to the dress JOÜAILLIER is wearing: https://collections.lacma.org/node/170609

Note Nicolas's flower gardener print

made me think of another dress I was making for

the collection Support Thoughts of Roses but there have been

many silk designs I have looked at as part of the research

for this project that are similarly covered in flowers

This portrait also by Nicolas de Larmessin I, https://www.invaluable.com/auction-lot/nicolas-de-larmessin-1684-1755-marie-josephe-de-s-11-c-d0ddf57c87 again in black and white, shows a dress that also, to my mind, might have been silver. Rather than being imagined this dress was real, but again it looks like it is covered in decoration that is three-dimensional. Perfect for someone needing a tactile experience of fashion.

Then there were the real silver dresses I was seeing on research visits. In fact it seemed I was meeting with silver dresses in each exhibition and on each visit I made.

At the Dressing the Georgians exhibition held at The Queens Gallery at Buckingham Palace in the Summer of 2023 I came across several other silver dresses and I was particularly interested to learn that it was the tradition across Europe for Royal brides to wear silver at this time. I was fascinated to see the raised decoration on this dress, which seemed comparable with Nicolas de Larmessin's engraving.

Gainsborough Dupont (1754-97) Caroline of Brunswick when Princess of Wales 1795-6 Oil on canvas

"Princess Caroline's nuptial robes followed the convention across Europe for royal brides to wear a silver grand habit, the most formal style of dress. The bodice and train are of silver tissue, the petticoat covered in silver net and small tassels. Cords were a practical feature of the court train, allowing it to be pulled up. The waistline is high reflecting the shape of fashionable gowns during the 1790s and the princess's hoop was noted by the press and being 'very small, such as it used for morning dress'. Pinned to the centre of the bodice is a miniature of her husband, the future George IV."

© The Royal Collection

Here is a a portrait of Princess Caroline during the wedding

1795 "John Graham, The Marriage of George, Prince of Wales and Princess Caroline of Brunswick "For formal court occasions such as royal weddings and birthdays, etiquette required quests to wear highly decorative but often old-fashioned styles of clothing rarely worn in other sittings. Here the Prince of Wales wears a blue velvet coat with standing collar and matching breeches, each richly embroidered with silver thread and spangles, and a waistcoat woven from silver thread.. In fashionable circles most men opted for simpler, more understated styles. Similarly, the noticeably wide skirt worn by the groom's mother Queen Charlotte (seated o the right), is created using a hoop petticoat. Such hoops were highly fashionable around the middle of the century but by the 1790s were considered distinctly outmoded."

© The Royal Collection

© The Royal Collection

And it was fascinating to note that the guests also wore silver, including George's Mother Queen Charlotte

© The Royal Collection

Queen Charlotte can be seen again here, when she was younger and George was small likewise in a beautiful silver gown

1764 - Johan Joseph Zoffany, "Queen Charlotte with her Two Eldest Sons, Oil on canvas, Seated at her dressing table with expensive lace, Queen Charlotte is formally attired for dinner, wearing an ivory coloured open gown with matching petticoat. The artist has skilfully represented the sheen of he queens dress to indicate it is satin-woven silk, a weaving technique that maximises the reflective nature of silk thread. Both princes wear fancy dress outfits which were recorded as having been ordered by their governess Lady Charlotte Finch, who is just visible in a mirror in the background. The one year old Prince Frederick (on the left) is in 'Turkish dress', including a turban and fur-lined gold kaftan complete with childhood leading strings, while Prince George (aged two) is dressed as Telemachus, a character from Greek mythology."

© The Royal Collection

Princess Charlotte, the daughter of George and Caroline, followed suit in a silver dress (that appears pink because of the reflection of the red walls surrounding it) at her own wedding:

"Wedding dress worn by Princess Charlotte,1816, silk, satin, silk net and metal thread RON71997. Princess Charlotte's gown follows the tradition across Europe of royal brides to wear silver. A close examination of the dress, alongside visual and documentary sources, reveals that it has been significantly altered from its original form, which is revealed in a print from the time . The shell ornamented borders of the sleeves appear to be original as they are described in the princess's wedding trousseau. These were then later combined with a different court gown, a demonstration of the practice for clothing to be remodelled."

© The Royal Collection

A stunning example of the tradition of Royal silver European wedding dresses is evidenced here in the gown worn by Marie-Antoinette from 1770

There were two other paintings of women in beautiful silver (or is one white?) silk gowns in the Dressing the Georgians exhibition.

© The Royal Collection

1742 - "William Denune, Portrait of a Woman. The first layer of the dress was the shift, a knee-length garment worn closet to the skin and usually made of washable linen, in this portrait the ruffled neckline is visible, as well as the voluminous sleeve at the sitter's right elbow. On top of this she wears a gown of heavy weight plain white silk, cut to fit tightly across the bodice. Representing female sitters in plain silks allowed artists to focus on depicting the play of light across the surface of the textile it was a convention established in the seventeenth century most notably by Sir Anthony van Dyck "

and

c.1740-6 "Antoine Pesne Fredericka, Duchess of Saxe-Weissenfels. The rick silk used to make this gown has been woven with a large-scale floral design against a background of metallic silver thread. Throughout the eighteenth century the French city of Lyons retained its reputation for producing the finest quality and widest range of silk fabrics in Europe rivalled only by the industry centred around Spitalfields in London, originally set up by Huguenot exiles from France. During the 1730s innovations in weaving techniques led by the French designer Jean Revel enabled subtle shading effects, resulting in more naturalistic and three-dimensional botanical motifs. Setting up the loom for a figured silk could take as long as six weeks. Surviving examples reveal the complexity of such silks which is sometimes not evident in portraits - here there silver background is woven with honeycomb and chevron patterns."

© The Royal Collection

Queen Anne - her style

Looking through all of the images below, but especially the last two I was looking at particular aspects of her dress, including the chain of state around the top of her bodice, the design of the sleeves, the shape of the skirt etc. In fact I would find the likeness carved in stone particularly interesting and helpful as regards my working out how to construct the necessary shapes from paper.

all these images are from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anne,_Queen_of_Great_Britain

where you can also read about poor Anne's 18 pregnancies:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anne,_Queen_of_Great_Britain

And there is more here: https://royalcentral.co.uk/features/stories-of-the-stuarts-queen-annes-18-pregnancies-47524/

So how to bring all of this together?

Design:

I did my initial sketch still with the ceiling of the chapel in mind for the raised decoration on the skirt but as soon as I stood beneath Hampton Court Palace's Queen Anne era chandelier and looked up (knowing she might have done the same) the design changed And so, as I was making I was also re-designing, to reflect this

Making

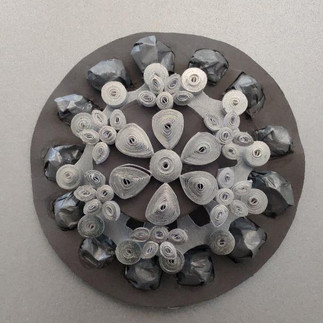

Using silver edged silver quilling papers and initially placing these on a dark grey background I would later incorporate a hint of gold and swop in the navy blue I mentioned above.

In between the raised vertical decoration there would be the plain silver panels of the skirt I thought. Then I cam across this image of Anne (above right) and fell for the beautiful gold embroidery on her skirt. So I decided to mirror the shapes of decoration we know she actually wore and to add a twist. Silver studs. For I feel that she would have needed, as a woman and as a Queen (and as someone that history speaks a tad unfavourably about) to have been somewhat armour plated.

Making the thistle for the centre of the stomacher was not easy. I tried various methods including silk thread wrapping shapes cut from card which is part of the art of the the practitioner of passementerie as you can read in my post Copper tulips

I tried stitching the thistle leaves using the sewing machine also

But for a long time nothing was either working in itself or giving me the look I wanted.

I had by this time also seen a Queen Anne era apron (below), with its beautiful embroidery, at Worthing Museum & Art Gallery and I wanted to incorporate the shapes, at the bottom of the stomacher below the thistle.

The parts of the thistle came together when the leaves became lighter weight, I sewed lace paper to recycled cardboard packaging for around the neckline and referred back to the chain of state I mention above for the version I was making. I hand twisted thick chords from thick gold silk thread, silver quilling and navy carboard. I looked also to mimic ermine by stitching in dark grey thread on white paper tablecloth.

Weaving Silk Stories is a new project in partnership with the independent charity Historic Royal Palaces, which is due to launch in 2027.

Paper sponsorship by Duni Global