1730s - research & making - Metamorphosis - mulberries in Fournier street

- Stephanie Smart

- 5 days ago

- 21 min read

Silk history

For a few years in the 1780s an Italian called Salvatore Bertezen lived in Kennington Lane on the outskirts of London. Bertezen had moved to England in order to drum up support for a scheme to establish sericulture (the raising of silk worms and the production of raw silk from their cocoons) there. In Kennington he grew mulberry trees, hatched and fed silk worms, collected their cocoons and reeled silk thread from them. He issued a pamphlet encouraging others to follow his example and provided practical information on the care of silk worms. Although this project now has the flavour of the eccentric about it, Bertezen was taken seriously: the British Library’s copy of his pamphlet comes from the collection of Sir Joseph Banks. His scheme was discussed at the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce and they awarded Bertezen’s silk a gold medal in 1783. In fact, the Italian’s efforts were part of a longer running interest within the Society about the possibilities of cultivating raw silk in England."

Royalty

George II - King of Great Britain and Ireland, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg (Hanover) and a prince-elector of the Holy Roman Empire from 1727 until his death in 1760. "When George II succeeded his father in 1727 the palace [Hampton Court Palace] entered its final phase as a royal residence. George and Caroline completed work on their apartments and started new works for the younger members of their large royal family. In 1734 Queen Caroline invited her favourite architect and designer William Kent to decorate the plain walls of the Queen’s Stairs. He created a Roman-style design, which included a tribute to Caroline, whom he compared to the ancient goddess Britannia." https://www.hrp.org.uk/hampton-court-palace/history-and-stories/the-story-of-hampton-court-palace/#gs.002yju

Mulberry trees were grown at Hampton Court Palace in fact. Not for silk worms but as part of Queen Mary's exoticks collection and also for the edible fruit. Working in association with Historic Royal Places that would prove significant in this instance.

When I started looking at what the men, at court, might have been wearing during this period, that is, when I started looking at suits from the 1730's in particular, I couldn't help but notice the size of the cuffs. Likewise I noted that in most cases I was seeing a beautiful, complementarily styled waistcoat. I also found it interesting to note the shape of the silhouette because, having already made a study of the dolman jacket designed to go over a Victorian lady's bustle, I saw a, differently shaped but similarly raised, back profile at this time for men. In my mind there was something of the preening male bird about this style of frockcoat with its beautiful backward pointing tail and the splendour of the fabrics used (most often silk or silk velvet)

This is a great page for a clear outline of the changes over this period of the shape of the back of the male coat: http://textileconservation.academicblogs.co.uk/drawn-from-history-deconstructing-menswear-silhouettes-from-historic-portraits/

There is a lovely side view of a pale blue velvet frockcoat from this period low down on this webpage: pagehttps://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1730-1739/

And here are a few other examples (please click on each image to be taken to its source)

Man’s coat of brown and blue silk from 1730s-1740, Image © National Museums Scotland.

A formal suit for courtly ceremonies, Italian 1720-1740 © Uffizi Gallery

Ensemble French 1730 © The Met

Europe, circa 1730 photo © Museum Associates / LACM

skirt/military state dress consisting of skirt, best, breeches Frederick Augustus King of Poland 1733

I like this portrait for the way that all of three elements (waistcoat, cuffs and flicked up back panel) seem to be being focused upon.

1736 Dutch Portrait of a Member of the Van der Mersch Family Cornelis Troost

And here is a fabulous example: https://collections.lacma.org/node/214509

waistcoats

Seventeenth and Eighteenth-Century Fashion in Detail by Avril Hart and Susan North, published by the V&A shows

a very noteworthy change as regards the outline design of a waistcoat in the 1730's. At that point it had sleeves! Please see the example they reference here: https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O13541/waistcoat-unknown/

The wider sleeves of the male coat during the 1730s (compared to the slim sleeved frock coats of the later 1740s - 1770s) allowed room for a waistcoat sleeve underneath. Because of this a man could have a second pair of matching (often equally beautifully decorated) cuffs under the enormous pair of cuffs on the frockcoat itself You can spot this in the painting above. The example shown in the link above is made of Spitalfields silk.

We can see here a gradual slimming of the sleeves and shrinking of the cuffs of men's frockcoats even during, but certainly in the years after, the 1740's. From this: https://www.facebook.com/groups/352566505697426/posts/1571606887126709/

And I wanted to include two examples of the backs of frockcoats from the 1740's which show that the area over the bottom became slightly flattened as time went on. With the side panels sticking up and back a little less. Another profile change that would continue over time.

Italian 1740–60 The Met (above)

But something that remained constant from the 1730's to the 1770's was the primary type of applied decoration. The technique of note was the embroidery of course. On male frockcoats I love to look at the pockets and the way the embroidery is made to fit the shape of the flap. By looking at this area you also get to zoom in on beautiful thread buttons. You can see more of my research into thread buttons here

And my favourite pocket embroidered pocket (from looking at which I would start designing my own) was this one: https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O127185/waistcoat-unknown/

These two links show impressively decorated examples of where male fashion had come from prior to 1730:

But ideally I needed to see a 1730's era jacket and waistcoat outfit in person. So I went with a friend to V&A East, having arranged a personal viewing. This is the outfit https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O34282/coat-unknown/?carousel-image=2015HU0775You I am constructing a page in The Hidden Wardrobe, my research image reference site with images from this trip and will publish soon so please do check back.

But how was I going to tie my research of 1730's male frock coats into a study of the history of silk in the UK and the lives of particular people from that time?

Well, the way my mind went first (strange as it may seem) was toward this stunning silk velvet Arts and Crafts woman's coat from 1895-1900, which I have long since wanted to use as inspiration for a garment of my own and which I have likewise long since adored for the sharp slightly pointy lines of its silhouette, as well as for the drama of it's colour. It seems to me to have the same line at the back as the 1730's male coat but this time extended to the floor. The impact of the dark (navy) velvet background and the light (gold) floral, and textured, decoration is significant.

The way that the shape of a natural form, the Umbellifer (which I see often dried and beige by the side of the road at the end of the summer), has been used here, makes for a garment that, I believe, is widely admired by those who study and love historical fashion. These are images I took of the coat several years ago in the fashion gallery at the V&A but if you click on any one of the images below you can see it in it's full glory on the V&A website.

Now was one of those times I thought I would surely be inspired by it! By the distinct colour contrast and its incorporation of nature anyway. But the Umbellifer (or Apiaceae) would not be the plant I would incorporate. In this instance that must surely that be the mulberry:

Mulberry:

"The black mulberry became associated, particularly in the East End, with the silk weaving industry, which was originally brought to England by Protestant Huguenot refugees from France in the time of Henry VIII in the early 16th century. This migration gathered pace in the 17th century, with extensive settlement in the East End – especially Bethnal Green, Bishopsgate Without and Spitalfields – making the area a major centre silk weaving centre. Silk weaving was carried out producing imported raw materials, but in the early sixteenth century, James VI and I, keen to promote the industry encouraged the widespread planting of mulberries in an attempt to end that dependence by providing a foodstuff for the silkworm. The attempt to produce British raw materials for the industry was largely unsuccessful. Despite this mulberries were still planted for ornamental purposes, being highly prized for their shade giving properties."

You can see some images of mulberries in art here: https://www.growables.org/information/TropicalFruit/MorusSppBotanicalArt.htm

English: Morus rubra L. - red mulberry - Duhamel du Monceau, H.L., Traité des arbres et arbustes, Nouvelle édition [Nouveau Duhamel], vol. 4: t. 23 (1809) [P.J. Redouté] drawing: P.J. Redouté lithograph Tassaert family: Moraceae subfamily: Moroideae tribe: Moreae 202746 ruber, rubra, rubrum 202746 ruber, rubra, rubrum Illustration contributed by: Real Jardín Botánico, Madrid, Spain id taxon: 5910 id species: 681624 id publication: 2099 id volume: 5626 id illustration: 250389 link to this page:

Strangely the flowers on the mulberry plant look more like a collection of silk worms than actual flowers!

"White mulberry (Morus alba L.) is a deciduous tree that originated in China, Japan, and India, but is now found worldwide. White mulberry has been used as a traditional herbal remedy since at least 3000 B.C. The leaves of the plant contain multiple biologically active compounds, including antioxidants, amino acids, and alkaloids, which may have beneficial health effects." -https://www.poison.org/articles/is-white-mulberry-poisonous

Today, in St James' Park you will find:

"...several wonderful mulberry trees, including one of the largest mature white mulberries in London, on a mound. Nearby and near to the footpath are three mature black mulberries. There is a young paper mulberry (Broussonetia papyrifera) on the mound, near to the white mulberry. There is a mature white mulberry by the Wellington memorial at Hyde park corner too. And 2 black mulberries. The trees are a reminder of King James l mulberry garden, which stood nearby (NW corner of Buckingham Palace and part of Green Park) in the the 17th century, planted to set an example in his effort to establish an English silk industry. The plan failed through lack of serious interest, as well as the cool, damp climate and lack of expertise in rearing silkworms on a commercial scale."

"James I...planted four acres of mulberry trees near the site of the future Buckingham Palace and had himself penned a preface to a silkworm book in which he offered magnanimous and friendly encouragement to the landed gentry to plant more 'food of the worms...that they be nourished and maintained.' While James prescribed ten thousand mulberry trees for each county of England, his queen, Anne of Denmark...commissioned an up-and-coming architect named Inigo Jones to design for her an elegant silkworm house, two storeys high...To these monarchs, bringing silkworm cultivation to England was a 'question of so great and public utility to our kingdom and subjects in general...' that they were quite 'content that our private benefit shall give way to the publique ' for 'such a work can have no other private end in us, but the desire of the welfare of our people'. it was an ambition that had seen great success in France, which England sought to emulate. But in Jacobean England it would ultimately abjectly fail , just as it would in the king's new colony of Jamestown, Virginia, though there the mulberry was superseded by tobacco, that other lucrative leaf, which would be even more enthusiastically adopted in England and its colonies"

p30 Silk, A history in three metamorphoses by Aarathi Prasad

While they weren't successfully cultivated en masse in Britain we do know that mulberry trees were once to be found growing on one of the most significant silk weaving related streets in London, Fournier Street thereby tying the tree even more tightly to my research for this project

"...formerly Church Street, was the last to be built on the estate, and contained, particularly on its south side...some of its best houses. The row of gardens at the back of the houses on the south side is the only one shown on the 1873–5 Ordnance Survey map of the district and the gardens contained mulberry and fig trees and vines into this century. But although the houses here, as elsewhere on this estate and also on the Tillard estate, were planned and constructed essentially for domestic occupation, a considerable number were soon occupied by firms connected with the silk industry. The building lease of the finest house in the street, No. 14, included, doubtless like those of other houses, a restrictive covenant respecting its use for noxious trades. But silk- or worsted-dyeing was specifically excluded from this restriction, and the house was occupied commercially, at least in part, as early as 1743. In this house, as in Spital Square, silk waste was packed between the floor joists, probably to deaden the sound of looms in the garret storey.

To read more about Fournier street please click: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fournier_Street

You can also better understand the importance of this street from my posts that relate to my research about the Huguenots

Throughout the research for this project I've been constantly looking, across images from many different historical periods and at items held by many different venues, for silk designs that include a visual representation of the mulberry. Because so many historical silk designs included flowers, fruits and leaves and because Huguenot silk weavers were growing mulberry trees in London themselves (even if not on a commercial scale) I felt quite quite hopeful about finding a silk design, from the 1700's or later, that would include the mulberry directly.

But I couldn't, the closest I think I came were elements of these two designs from the archives at Macclesfield Silk Museum which look a little like the fruits and the silk caterpillar's cocoons:

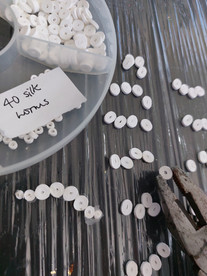

Mulberry shaped buttons however...

...they existed:

The closest are these on a doublet from the 1620's https://perthmuseum.co.uk/star-object/silk-doublet/ But Macclesfield Silk Museum has some that are similar:

So from there we started developing our own. These were made by House of Embroidered Paper volunteer Kerry

Mulberry leaves are, of course, the food of the (hard) working silk worm/caterpillar Bombyx mori which transmutes into a small white moth having produced the thread needed to weave the fabric the history of which is the focus of this collection. In the images below you can see this white silk worm (caterpillar).

The fuzzy green caterpillar is that of the giant coloured moths who produce silk only for their own use in warm climates. I visited the Natural History Museum in London to see specimens of all the types of moths that create silk. You can see images from my visit here. And I delve into the process of their metamorphosis (the title of this piece) further in my post on silk.

By this point in the research I believed I was seeing caterpillars themselves actually in decoration on the examples of historic fashion I was looking at. Was I imagining things? These two links take you to chorded/decorated garments from the 1600's held in the collection at the V&A.

Can you see caterpillars (illustrated or implied)?

And below you can see an Eighteenth century Polonaise gown, held at Worthing Museum.

I see caterpillars in the decoration of this gown too, do you?

Then I stumbled across an image that would prove I wasn't seeing things.

This painting shows a gown with extraordinary sleeves (leg of mutton or gigot as they were known) covered in purposefully portrayed squiggly silk worms picked out in white and silver thread just as I was planning, though here the ground is pale. And on her skirt...those are apparently mulberry leaves.

The woman in the dress is Elizabeth I? You might think so but there is debate. In relation to the quote I include above about the silkworm breeding ambitions of the royalty of the late 1600's possibly this is in fact Queen Anna of Denmark Queen Consort to Elizabeth's successor James VI and I. Promotion of the ambition of an era, a British silk industry, home grown, from leaf, to caterpillar, to moth, to thread, to woven fabric shown in paint depicting a silken dress,

Note: The love of the silkworm in Britain is also evidenced by this poem:

All in all there appeared to be a precedent for my deciding to apply decoration to this frockcoat inspired by the working silk moth itself. And with their ridged, twisted bodies I thought at first that it would be quite easy to mimic the shape of the silk worm's body. I thought simply to use silk thread from Whitchurch Silk Mill But in this case the technique would prove a detour

I needed more research, to integrate into my final design in order to rework this imagery. I had my style, my era, and my specific botanical inspiration. I needed to clarify the bold colour combination I knew from the Umbellifer coat that I was going for. But I also knew it wasn't to be navy and gold. Surely instead I had to use white (to be silk worm related) black seemed the obvious contrast but I needed the research to take me there specifically. Ideally I also wanted some individuals from the early 1700s whose life stories I could weave into the final design.

To recreate the mulberry leaf shape I thought I would be looking to paper made from the mulberry tree which I had found on Etsy:

"This ultra-soft mulberry paper...so lovely, thick and rich...with its own leaf content...crafted from the bark of the Mulberry Tree. Mulberry papers are known by many names including Kozo, Rice Paper, Hanji and Unryu. The long fibers of mulberry paper gives it a soft feel, yet maintains a durability not found in traditional papers. Tear the edges of Mulberry Kozo Paper to get a soft, feathered, deckled edge..."

Especially when I found some with the skeletons of actual leaves embedded. But I found myself more intrigued by the dead skeletons themselves in the end and so that would be where I'd land.

Black and white

To hone down the colour contrast I looked again at my research for other pieces.

Eye sight loss - I have touched on the eye sight loss suffered by silk mill workers and workers in other posts, including Queen Anne's Silver. Black and white is apparently a colour combination found to be beneficial to some people today with certain types (and degrees) of eye sight loss. And I had started this collection planning to try to consider, across the Weaving Silk Stories collection, people suffereing

© The Museum of London

Pearly Royalty -The practise of decorating a black suit with white pearl buttons is credited to the first Pearly King Henry Croft. It turns out he died in 1930 and whilst making a 1730's jacket I thought it would be nice to nod toward his life, over that 200 year time gap. Then I read that Henry Croft was anyway building (or stitching) on an older tradition, that of the Costermongers.

"Costermongers...were said to have sewn mother-of-pearl buttons on to their clothes to distinguish themselves; a line down outside seam of their trouser legs from knee to ankle as well as on the flaps of their jacket pockets. It was a tradition for each coster community in London to elect a leader, or ‘King’ to organize them, keep the peace and stand up for their rights with authorities..."

"Pearly Kings & Queens originated in the 19th century from the 'Coster Kings & Queens', who originated in the 18th century, who originated from the 'Costermongers', who originated from London's 'Street Traders', who have been around for over a 1000 years...Street traders, or 'Costermongers' as they became known, have been an important feature of London life since the 11th century - and for the best part of 900 of those years they were unlicensed and itinerant - at times hounded by the authorities & bureaucracy. They cried their wares to attract customers with vigour and panache - much to the annoyance of London's 'well-to-do' society - yet they provided an essential service to London's poor; mainly selling their wares in small quantities around the streets & alleyways - at first from baskets, then progressing to barrows - then permanent static pitches from stalls - until they finally evolved into today's familiar and popular Markets...Because of London's unique geographical position it grew and thrived as a trading centre - the City grew up not just around its financial market, but around its famous markets that provided the necessities of life - markets such as Billingsgate (where the fish were landed), Smithfield (for cattle & livestock) and Covent Garden and Spitalfields (for fruit, veg & flowers)

"London based costermongers had their own dress code. In the mid-nineteenth century, men wore long waistcoats of sandy coloured corduroy with buttons of brass or shiny mother of pearl. Trousers, also made of corduroy, had the distinctive bell-bottomed leg. Footwear was often decorated with a motif of roses, hearts and thistles. Neckerchiefs—called king's men—were of green silk or red and blue...Henry Mayhew gave a detailed description of the costermonger's attire.

"The costermonger's ordinary costume partakes of the durability of the warehouseman's, with the quaintness of that of the stable-boy. A well-to-do 'coster,' when dressed for the day's work, usually wears a small cloth cap, a little on one side. A close-fitting worsted tie-up skull-cap, is very fashionable, just now, among the class, and ringlets at the temples are looked up to as the height of elegance. Hats they never wear—excepting on Sunday—on account of their baskets being frequently carried on their heads... Their waistcoats, which are of a broad-ribbed corduroy, with fustian back and sleeves, being made as long as a groom's, and buttoned up nearly to the throat. If the corduroy be of a light sandy colour, then plain brass, or sporting buttons, with raised fox's or stag's heads upon them—or else black bone- buttons, with a lower-pattern—ornament the front; but if the cord be of a dark rat-skin hue, then mother-of-pearl buttons are preferred. Two large pockets—sometimes four—with huge flaps or lappels, like those in a shooting- coat, are commonly worn... The costermonger, however, prides himself most of all upon his neckerchief and boots. Men, women, boys and girls, all have a passion for these articles... The costermonger's love of a good strong boot is a singular prejudice that runs throughout the whole class." Costers were especially fond of mother-of-pearl buttons. Men decorated the legs of their trousers with a line of pearly buttons. By the 19th century, both men and women began adding these pearly buttons to their clothing as James Greenwood describes. "Any one, however, who knew the significance of; and took into consideration the extraordinary number of mother-o'-pearl buttons that adorned the waistcoat and well-worn fustian jacket of the gentleman in question, would have been at once aware that he was somebody of consequence in costerdom, at all events... The pearl button is with him a symbol of position and standing, and by the number of glistening rows that rather for ornament than use, decorate his vestment, his importance amongst his own class may be measured." "

So it sounds like the 1730's are when the tradition began!

I wasn't going to pretend to be making garments to mimic the style of the Pearly Kings and Queens but I knew I would be holding them in mind regarding colours and pearlescence and in terms of sheer wonderful exuberance as I went on with Metamorphosis, as they had succeeded in transforming themselves into the glittering royalty of trade on London's streets.

For more on the Pearly Kings and Queens please click here

Or have a look at these sites:

- https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20221101-the-pearly-kings-and-queens-londons-other-royal-family

It made me smile to see that, though the accompanying text beside this painting says George IV ( in1795) is wearing navy and white/silver here at his wedding, the final look appears to me very similar to the outfit of a Pearly King

Detail from the oil painting The Marriage of George, Prince of Wales to Princess Caroline of Brunswick 1795 by John Graham seen at the Dressing the Georgians exhibition held in The Queens Gallery at Buckingham palace in the summer of 2023

To find out more about this painting and to see what Queen Caroline was wearing please see my post Queen Anne Silver

And what about these beautiful jackets from the end of that century all with black backgrounds:

Silk Queens

Interestingly, also in the 1930's the silk industry in Macclesfield was crowning it's own royalty.. Please Click here to watch a video of the crowning of Britain's silk queen in1933-'34. And here for a photo of a lady's great aunt who was silk queen in 1932.

Of royalty itself I was to find other links that cemented the idea of a black background:

Mary Delaney - A member of the royal court in the 1700's Mary Delaney created beautiful botanical imagery on a black background. You can read more about Mary in a previous post I wrote here, when I visited the British Museum to see some of her paper cut flowers which date largely to the 1770's and 1780's. But I wanted to pick up to a greater degree on something I had mentioned in that post, a link she had made herself, between paper cuts and fashion. Prior to creating the majority of her paper cut flowers she had in fact been designing botanical imagery for embroidery: Below you can see...

"...bits of the petticoat, which dates from about 1739/1740, have been preserved in an almost pristine state and been passed down the generations. Clothes defined status and social standing, and in this case, in conjunction with Mary’s many letters, give an insight into not only how fashions change but importantly how flowers and plants were perceived and appreciated...There’s no doubt that Mrs Delany was interested in fashion, and her correspondence includes many comments on what people wore, and sometimes includes a description of what she herself wore, and there are often floral elements included. In 1734, for example, she wrote an account of her outfit for the wedding of Princess Ann to the Prince of Orange: ”Tis a brocaded lutestring, white ground with great ramping flowers in shades of purples, reds and greens… it looks better than it describes, and will make a show.” Black was an unusual colour choice, because the fashion was definitely for pale coloured fabrics which were thought to allow for greater contrasts between light and shadow in the fabric’s drapery as it moved. Although it’s usually associated with mourning, in Mary’s case her unlamented husband had been dead for about 15 years so its much more likely wearing something this ornate, probably with a lighter coloured gown on top was simply a bold fashion statement. She adopted the same technique when in later life she created her botanical collages, laying them out on a black background."

"Godfrey Smith’s Laboratory or School of Arts published in 1756 gives a good idea of how drawings were translated onto fabric at this time." - https://thegardenstrust.blog/2018/07/07/mrs-delanys-petticoat/

The rest of my research would prove to me that it was rare indeed for female fashion to incorporate a black silk background, other than for mourning dress but it would only increase the incidence of my finding images of male black backed fashion from the 1700's.

People

Maria Sibylla Merian - I wanted also to speak about Maria Sibylla Merian in a bit more depth here though I mention her in passing in other posts related to other pieces in this collection also. In relation to this piece I decided I needed to make a visit to the British Museum.

"Not only was Maria Sibylla Merian (1647–1717) a fine artist...but she was a leading entomologist who transformed the way we understand the life cycles of insects. Before [her the] widespread belief was that insects were creatures born by spontaneous generation from mud, and few understood how caterpillars metamorphosed into butterflies and moths. This changed because of Merian’s painstaking work observing live insects, piecing together their life cycles, then expressing those in the most superb paintings. As if that wasn’t enough, she travelled to the former Dutch colony of Surinam, in the north of South America, now part of the Republic of Suriname, where she painted a huge catalogue of insects, plants, and other living organisms..."

M.S.Merian, Metamophosis of a the silk moth (Bombyx mori), https://issuu.com/accpublishinggroup/docs/mariasibyllamerian_blad

Maria studied silk worms extensively.

"'Most esteemed reader and lover of the arts', her [book] Wondrous transformation began, 'while I have always endeavoured to adorn my flower paintings with caterpillars...and small creatures of that kind...I have also often taken the trouble to collect them; until eventually, by observing the silkworm, I became aware of the caterpillar's changes and began thinking about them, and whether that very same kind of transformation might occur in others as well. Since then, after diligent and painstaking investigation, I concluded that their manner and type of change is nearly identical; the difference is that silkworms spin useful filaments while...others spin themselves up like a a silkworm and produce exactly the same kind of capsules encased in silk, although not as strong as that of the silkworm.' By then, her extensive observations had shown her that the metamorphosis of the silkworm easily exemplified the metamorphosis of similar insects. By using the already 'familiar so-called silkworm...' she felt, ' almost all the transformations and changes of...caterpillars...will be more readily understood.'"

p25 Silk, a history in three Metamorphoses by Aarathi Prasad

© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

All of her illustrations are beautiful do browse them here: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG38183

One hundred years or so after Maria Sibylla Merian published her caterpillar books, until the Swedish taxonomist Carl Linnaeus and his followers used her depictions of the natural world to name at least one hundred species, Merian had never separated the insects she studied from the plants upon which they depended, plants which would come to define them. Linnaeus himself would give the silkworm she observed in Frankfurt the scientific name Bombyx mori. Bombyx denoting that this was an insect of the family of moths called Bombycidae; and mori, honouring,...that this caterpillars natural food source were the leaves of Morus, the Mulberry tree."

p28 Silk a history in three metamorphosis by Aarathi Prasad

Maria Sibylla Merian Metamorphosis of the Lappet (after 1679) Wikimedia commons

It was fascinating to see illustrations of these extraordinary looking caterpillars alive, having seen their kin preserved at the Natural History Museum

For a huge resource of her images please click here

You can also see her work here

But it was upon seeing her black and white illustrations that I became particularly excited in terms of actually integrating her imagery into this frockcoat and waistcoat combination, which was to be called Metamorphosis. I saw them first at https://library.chethams.com/blog/the-wondrous-transformation-of-caterpillars-and-their-remarkable-diet-of-flowers/

For it's symmetry (as well as the lovely chewed leaves) I was inclined to settle my focus on this one, but I still had some experimenting to do with materials

And the wearing of this frockcoat was to be attributed to a particular person also but he is yet to be revealed.

Making

Having abandoned twisted silk I experimented with paper quilling for the silk worm bodies.

When I added pearlized white nail varnish to the shapes I was away.

And just as the pearly Kings and Queens cover themselves in pearls so I wasn't going to stop there. Mimicking the shapes of aspects of the mulberries themselves House of Embroidered Paper volunteers Denise and Marie and I made 82 of the dark green buttons with pearlized centres.

We lost a row for the pale green version shown in the row above but regained it and flattened the design for a third all white variation below of which there needed to be 53, each made with 24 roundels for the outer row made from only an 1'8th of a strip of quilling paper

I'd collected two different shaped leaves from one mulberry tree in the French Hospital – Huguenot Almshouses in Rochester

and started drawing around them, then I ordered skeleton leaves and sprayed them silver. I allowed myself a third colour which, given the links to nature in this piece, had to be green.

Then I made a trip to V&A East to see a couple of jackets from the 1730's in person, so as to understand better their construction. And then I began!

Weaving Silk Stories is a new project in partnership with the independent charity Historic Royal Palaces, which is due to launch in 2027.

Paper sponsorship by Duni Global